Megaliths - huge, upright stones and lintels - are generally considered products of sedentary agricultural societies, rooted to the land and with the manpower and social structure available to move and raise huge boulders often sources from hundreds of miles away. If they are seen as monuments to their ancestors, perhaps those who first cleared the trees and tilled the first fields, then there would be no reason to think that something of a similar nature was created by the people who came before; the hunter-gatherers.

However, the sprawling expanse of monumental structures found across the Tas Tepler or Stone Hills of south-eastern Turkey , the most famous being Gobekli Tepe or Potbelly Hill, argues otherwise. Each one was built by a hunter-gatherer society with little to no knowledge of intensive plant cultivation. Far from being too busy in hunting and gathering to built anything that could last, the people of the Tas Tepler clearly had extensive social and material worlds that went beyond basic subsistence.

If non-farmers in Turkey, 11,000 years ago, could make something whose only parallel is with Stonehenge or the later monuments of Old Kingdom Egypt, what about the rest of hunter-gatherer Europe?

To explore this, we need to look at the beginnings of monumentality itself.

Ice Age Monuments

Structures of a monumental size, did exist well before the end of the last ice age. The most famous of these early structures is in Kostenki 111, a roughly 25,000 year old site with a huge mammoth-bone building that must have taken weeks, if not months, to construct.

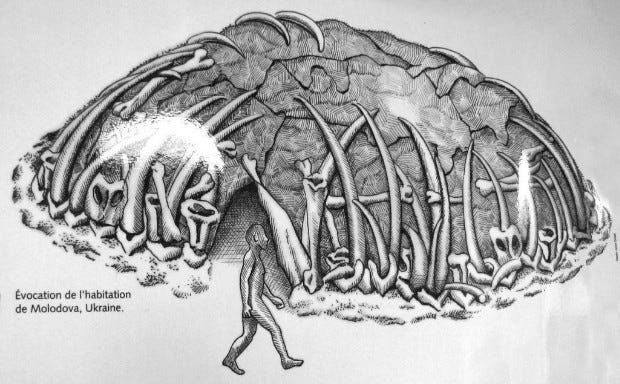

Smaller-scale versions of this are even found with the Neandertals of Molodova, south-western Ukraine, who 50,000 years earlier in central France also constructed two rings of stalagmites deep inside a cave which have sometimes been called a ‘mini-Stonehenge’. In the cave of La Ferassie, in northern France, a number of substantial burial mounds were dug from the cave earth, with the purpose of interring children and other sub-adults2. This was over 40,000 years ago, making them the oldest burial mounds in existence.

Of course, the rich cave art of the Upper Palaeolithic could be considered monuments in themselves, although an overwhelming amount evidence points towards them only being visible for a select few, rather than a central point in the wider landscape. This emphasis is, on the other hand, seen with the 28,000 years old burial of a young man in Paviland Cave, south Wales, which is stated on a high cliff that could be seen for dozens of miles around.

Wood for the Trees

The major change from the Palaeolithic to the Mesolithic was the transformation of the landscape from a largely treeless steppe to a richly wooded expanse of uplands, lowlands, rivers and wetlands. Mithen (1999) has argued that with all the trees and the abundance of small game, the large social groupings which were responsible for the art and monuments of the Ice Age were no longer needed, and thus artwork and monumentality largely disappeared. Indeed, there is very little in stone save for a few dubious animal carvings and a scattering of pigment-paintings on rock surfaces in Scandinavia3.

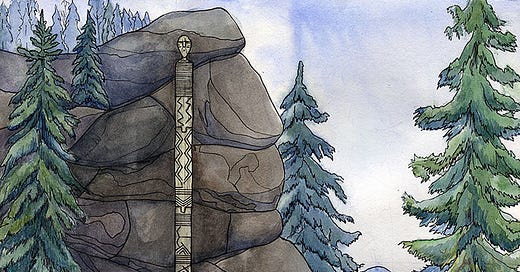

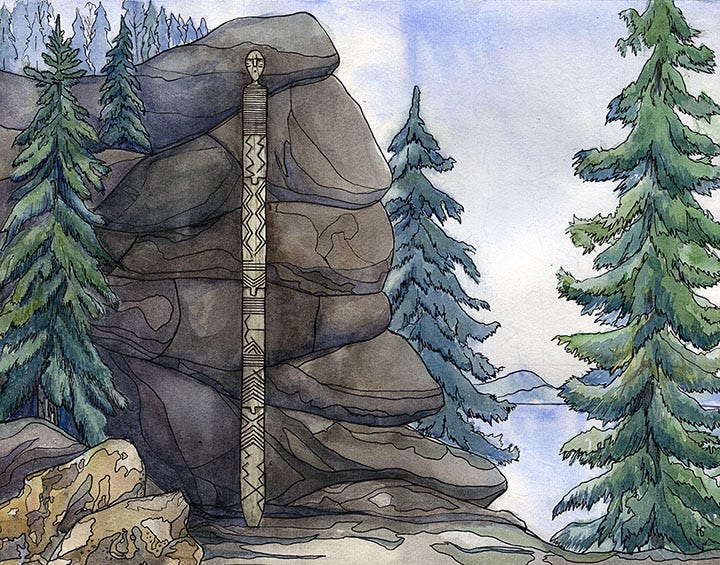

Yet , breakthroughs over the last decade have challenged this. A wooden idol more than 5 metres tall was unearthed at the turn of the 20th century in central Siberia, near the village of Shigir. While the statue is intact, several other fragments and an assortment of related artefacts have inspired a number of interpretations as to what the Shigir Idol actually looked like. Only in 2018 was the core of the idol given an approximate felling date of 10,200 BP,4 more than twice the age of Stonehenge and other megalithic structures.

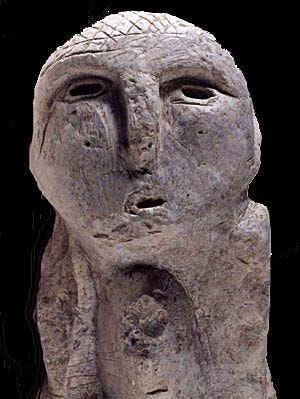

ian scholars have pointed out that there is a lot of similarity between the Shigir Idol and ethnographically recent wooden carvings of the Mansi people, who inhabit the same broad area. These more modern carvings are forest-guardians, made to keep harm at bay for a community or household, specifically during rites or certain times of the year. Some of the schematic features - the flat, t-browed face, the long, sinuous body, the appearance of other faces at points on the statue, and the presence of geometric grooves and carvings - also show up on a lot of later prehistoric statues and artwork, from the Yamnaya culture to the ‘Deer Stones’ of the Mongolian Iron Age5.

Given all this, the Shigir Idol probably represents just the tip of an iceberg of monumental tradition that was expressed entirely in wood and perishable material, one which only survived through chance or through translation, as at across the Tas Tepler, into stone.

One Turkish professor, Semih Güneri, even hypothesis that the Tas Tepler monuments were directly influenced by the stylistic repertoire of south-central Siberia that the Shigir Idol was a part of. This apparently extended beyond art to tool technology and subsistence6. While this remains a tentative theory, there is undoubtedly an eerier similarity between the schematic face of the Shigir Idol and faces carved in stone at Karahan Tepe and elsewhere.

If so, can we see it elsewhere in Mesolithic Europe?

Idols and Monsters

Despite the mundane archaeological record they’ve left behind, Mesolithic peoples must have had every right to be incredibly spiritual. The great beasts that their ancestors hunted were no more; comets and volcanic eruptions came from every direction; an entire landmass between Britain and Denmark flooded in the space of a day. As Astrid Nyland has argued, there might have been horrible monsters in the Mesolithic, lurking in the imagination of the old and young alike as they went about their lives in an ever-changing landscape of forests, rivers and cliffs.

A good way of warding off this shape-shifting evil, of rooting communities in familiar places, of remembering ancestors and heroes lost to legend, and of displaying the status of a tribe or family, would be to raise a monument. On the fringes of the Mesolithic world, there is in fact monumentality to be seen.

In Finland, spread across northern Ostrobothnia are vast stone enclosures known as Jätinkirkko or Giant’s Churches. From associated artefacts they were last in use in the region’s long transition to an agricultural way of life, approximately 2000 BCE, although they may have had much longer lives. Their function is still a mystery - explanations range from practical gathering-places to astronomical observatories - but at the time they would have been close to the coast, and were used by the ceramic-producing, seal-hunting Pöljä culture.

On the floor of the Sicily Channel between the Sicily and Tunisia, a seafloor survey uncovered a huge megalith chiselled with three holes along its side. Not only is it one of the largest megaliths known, sea-level modelling suggests a date of before 9,800 BP, when the bank it stood one would have been an island, and after which the stone would have been underwater.

Nor is this an isolated case. One megalithic upright at the Quinta la Quemada site in western Portugal returned an optical luminesce date of 7,900 BCE, or just after ten thousand years ago7. A Mesolithic burial at Auneau, in western France, was covered with boulders weighing more than 300kg, while massive stone piles were raised beside the Mesolithic graves found on the islands of Hoedic and Teviec.

Green Giants

So far, nothing like the Shigir Idol has been found. On the other hand, in Britain and a number of pits and post-holes have been found with charcoal present, indicating a tall pole made of larch or pine once occupied it. These have some relation to later Neolithic monuments, for instance with the passage tomb of Bryn Celli Du, where Mesolithic totem-pole-like beams were erected around 5900 BCE, right outside the future entrance8.

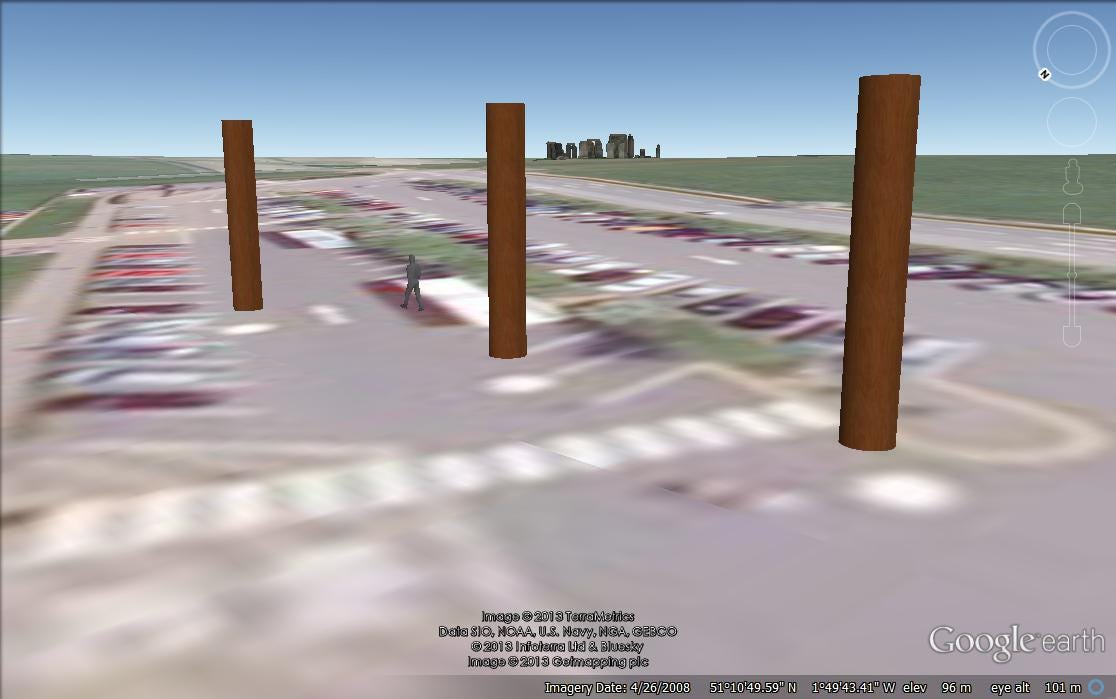

A row of post-holes close to Stonehenge have also been identified as being Middle-Mesolithic in origin, probably sockets for beams roughly arranged in a linear fashion. On top of this, an earthen mound also near the site has been dated to 8,000 BCE.

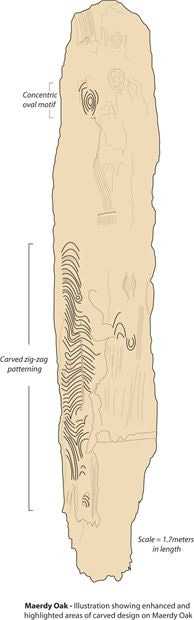

Only one fragment of solid evidence has survived. This is a 6,200 year old waterlogged piece of wood, 1.7m long, of what would have been a carved wooden post, and it was only recovered thanks to the development of a wind farm. This find - dredged from Maerdy, Glamorgan - features a row of parallel, sloping grooves and a kind of oval ‘eye’ carved near the top9. It can easily be seen as the Shigir Idol’s poorer cousin. Although, given its vastly different context it probably had a different purpose to the people that made it.

While there is little way to know what these monuments - if they were considered such - were for, there is a possibility that Stonehenge, and other prehistoric mounds, circles, ditches and stone circles, was placed there on the foundations of a monumental tradition that had been with the hunter-gatherers of western Europe for millennia; one that had once spanned from the Atlantic to the Ural Mountains.

Pryor, A. J., Beresford-Jones, D. G., Dudin, A. E., Ikonnikova, E. M., Hoffecker, J. F., & Gamble, C. (2020). The chronology and function of a new circular mammoth-bone structure at Kostenki 11. Antiquity, 94(374), 323-341.

Balzeau, A., Turq, A., Talamo, S., Daujeard, C., Guérin, G., Welker, F., ... & Gómez-Olivencia, A. (2020). Pluridisciplinary evidence for burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal child. Scientific reports, 10(1), 1-10.

Goldhahn, J. (2021). On the chronology and use of hunter gatherer rock painting sites in northern Europe. Perspectives on Differences in Rock Art, 7-42.

Zhilin, M., Savchenko, S., Hansen, S., Heussner, K. U., & Terberger, T. (2018). Early art in the Urals: new research on the wooden sculpture from Shigir. antiquity, 92(362), 334-350.

Bobrov, V. (2021). Shigir idol: Origin of monumental sculpture and ideas about the ways of preservation of the representational tradition. Quaternary International, 573, 38-48.

https://arkeonews.net/the-migration-movement-that-started-from-siberia-30000-years-ago-may-have-shaped-gobeklitepe/

Lopez-Romero, Elias. (2011). OSL dating of megalithic monuments: context and perspectives. p210

Burrow, S. (2010). Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey: alignment, construction, date, and ritual. In Proceedings of the prehistoric Society (Vol. 76, pp. 249-270). Cambridge University Press. p255.

Conneller, Chantal. "The last hunters: The Final Mesolithic, 5000–4000 BC." In The Mesolithic in Britain, pp. 356-419. Routledge, 2021. p417.